Abstract | Introduction | Presentation | Diversity | Main marine currents | The different oceanic zones : Summary of the species - Marine currents and other maps | Cosmopolitanism and endemism |

Species indicative of continental drift | Species whose localization is difficult to explain | Anthropic mechanisms | Conclusion

The different oceanic zones : Summary of the species - Marine currents and other maps The different oceanic zones : Summary of the species - Marine currents and other maps

If we consider the three main oceans ( Mediterranean , Red Sea , Antarctic and Arctic excluded) we obtain (2554 named forms only) (values updated in real time starting from the information stored in the database):

Atlantic: Calanoida = 1049; other orders = 302; Total = 1351 (52.9 %)

Indian: Calanoida = 773; other orders = 190; Total = 963 (37.7 %)

Pacific: Calanoida = 1265; other orders = 329; Total = 1594 (62.4 %)

Common species to the three main oceans: 568 (22.2 %), with Calanoida = 440 (17.2 %) and other orders = 128 (5 %).

Occurence of species in only one Ocean : Calanoida = 1061 (41.5 %), other orders = 280 (11 %).

The following tables summarise for the various oceanic zones concerned: the total number of species (named forms only) and their percentage with respect to all copepod species, and the percentage with respect to the total number of species in the zone (ind.: indicates forms without a denomination cited as sp. by authors).

Zones: Indian Ocean (16)  ; Red Sea (15) ; Red Sea (15)

|

16 |

15 |

Total species: |

963 (37.5 %) (+ 30 ind.) |

280 (10.9 %) (0 ind.) |

Calanoida: |

773 |

156 |

other orders |

190 |

124 |

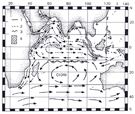

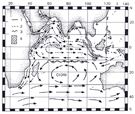

Issued from : T.S.S. Rao in Zoogeography of the Indian Ocean. Edis.: S. Van der Spoel & A.C. Pierrot-Bults, 1979. [p.255, Fig.1]

Issued from : T.S.S. Rao in Zoogeography of the Indian Ocean. Edis.: S. Van der Spoel & A.C. Pierrot-Bults, 1979. [p.255, Fig.1]

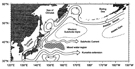

Surface currents in the Indian Ocean. 1 = SW monsoon, 2 = NE monsoon, 3 = Hydrothermal Front, 4 = Upwelling.

Sewell (1948, p.435) recorded 270 known species in the Indian Ocean. Of the 56 endemic species he reported (Sewell 1948, p.429), 26 have never been reported in any other ocean and 15 are known from a geographical extension encroaching upon neighbouring geographical zones . 486 species are also found in the Indo-Malay archipelago, i.e. 48.9 %

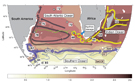

A schematic representation of identified current branches during the Southwest Monsoon, including some choke point transport numbers (Sv=106m3s-1). Current branches indicated are the South Equatorial Current (SEC), South Equatorial Countercurrent (SECC), Northeast and Southeast Madagascar Current (NEMC and SEMC), East African Coast Current (EACC), Somali Current (SC), Southern Gyre (SG) and Great Whirl (GW) and associated upwelling wedges, Socotra Eddy (SE), Ras al Hadd

Jet (RHJ) and upwelling wedges off Oman, West Indian Coast Current (WICC), Laccadive High and Low (LH and LL), East Indian Coast Current (EICC), Southwest and Northeast Monsoon Current (SMC and NMC), South Java Current (JC) and Leeuwin Current

(LC). A schematic representation of identified current branches during the Southwest Monsoon, including some choke point transport numbers (Sv=106m3s-1). Current branches indicated are the South Equatorial Current (SEC), South Equatorial Countercurrent (SECC), Northeast and Southeast Madagascar Current (NEMC and SEMC), East African Coast Current (EACC), Somali Current (SC), Southern Gyre (SG) and Great Whirl (GW) and associated upwelling wedges, Socotra Eddy (SE), Ras al Hadd

Jet (RHJ) and upwelling wedges off Oman, West Indian Coast Current (WICC), Laccadive High and Low (LH and LL), East Indian Coast Current (EICC), Southwest and Northeast Monsoon Current (SMC and NMC), South Java Current (JC) and Leeuwin Current

(LC).

Issued from : F.A. Schott & J.P. McCreary Jr. in Progress in Oceanography: An Annual Review, 2001, 51. [p.13, Fig.8].

A schematic representation of identified current branches during the Northeast Monsoon, including some choke point transport numbers (Sv=106m3s-1). See figure above for acronyms. A schematic representation of identified current branches during the Northeast Monsoon, including some choke point transport numbers (Sv=106m3s-1). See figure above for acronyms.

Issued from : F.A. Schott & J.P. McCreary Jr. in Progress in Oceanography: An Annual Review, 2001, 51. [p.14, Fig.9].

Schematic diagram of the Somali Current upper-layer flow patterns over the course of the year. Also marked are undercurrents as presently known (after Schott et al., 1990, with revisions). See figure above for acronyms. Schematic diagram of the Somali Current upper-layer flow patterns over the course of the year. Also marked are undercurrents as presently known (after Schott et al., 1990, with revisions). See figure above for acronyms.

Issued from : F.A. Schott & J.P. McCreary Jr. in Progress in Oceanography: An Annual Review, 2001, 51. [p.39, Fig.32].

Major currents and circulation patterns around Australia. Major currents and circulation patterns around Australia.

The continent is bounded by the pacific ocean to the east, the indian Ocean to the west and the Southern Ocean to the south.

Issued from : E.S. Poloczanska & al. in Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review, 2007, 45. [p.409, Fig.2].

Figure courtesy of S. Condie/CSIRO.

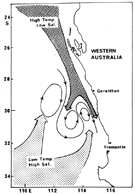

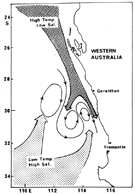

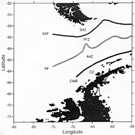

Representation of the major features of the circulation of the southeastern Indian Ocean. Representation of the major features of the circulation of the southeastern Indian Ocean.

Geopotential anomaly contours (full line) after Wyrtki (1961), (dotted) after Andrews (1975, 1977), and the Leeuwin Current modified from Cresswell & Golding (1980, dashed) are surimposed on the known extent of the larval distribution of Panulirus cygnus shown as a shaded area.

Issued from : B.F. Phillips in Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Ann. Rev., 1981, 19. [p.31, Fig.21].

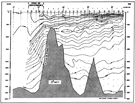

Idealized representation of the two major water types found in the southeastern Indian Ocean (after Kitani, 1977). Idealized representation of the two major water types found in the southeastern Indian Ocean (after Kitani, 1977).

B.F. Phillips in Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Ann. Rev., 1981, 19. [p.30, Fig.20].

Courants de l'Océan Indien :

Courant équatorial :

Au sud de l'équateur, au niveau du 10° de latitude Sud, le mouvement général des eaux dessine un vaste circuit cyclonique, tout à fait comparable à celui des autres océans.

Le courant Sud-équatorial se dirige de l'Est vers l'Ouest, parallèlement à l'équateur. Ce courant, dont la vitesse est de 20 à 25 milles par jour, ne dépasse jamais l'équateur. Sa limite Nord, qui varie comme celui des alizés du Sud-Est, est en général comprise entre 4 et 10° Sud. Sa limite Sud s'étend en certains points jusqu'au 25ème parallèle (parallèle du Sud de Madagascar). La masse énorme des eaux qu'il transporte, en avançant vers l'Ouest, se trouve contrariée par l'obstacle que représente Madagascar. Elle commence à se diviser près des îles de La Réunion et Maurice : une branche passe au Nord de Madagascar, l'autre au Sud.

Courant du Mozambique :

La branche Nord du courant équatorial, qui contourne le Cap d'Ambre (Madagascar) à une vitesse vers l'Ouest de 1 à 3 nœuds, arrive à la côte d'Afrique à la hauteur du Cap Delgado, situé approximativement sur le parallèle du Cap d'Ambre. Une partie s'infléchit vers le Sud-Ouest et devient le courant du Mozambique, qui longe la côte d'Afrique, et dont le débit et la vitesse diffèrent suivant la saison. Le courant est beaucoup plus régulier et plus fort pendant la mousson du Nord-Est de l'hémisphère Nord (de novembre à janvier, sa vitesse atteint 1 nœud, tandis qu 'elle n'est que d'un demi-nœud de mai à juillet).

Courant des Aiguilles :

La branche Sud du courant équatorial passe au Sud de Madagascar à une vitesse d'un demi-nœud, et va rejoindre, à la hauteur de Natal, le courant du Mozambique. Leur réunion forme le courant des Aiguilles, qui se fait sentir jusqu'à une distance de 120 milles de terre, et qui transporte jusqu'au Cap de Bonne-Espérance des eaux relativement chaudes.

Ce courant des Aiguilles, un des plus violents des courants océaniques, est aussi l'un des plus constants. Le long de la côte du Natal sa vitesse atteint 4 nœuds, parfois 5, et rarement inférieure à 2 nœuds.

Le courant des Aiguilles ne paraît pas présenter une variation annuelle régulière en volume, en force ou en direction. Peut-être est-il un peu moins fort en juillet, au moment où souffle dans le Nord de l'Océan Indien la mousson de Sud-Ouest, et où le courant du Mozambique, qui l'alimente en partie, est plus faible.

Les coups de vent d'Ouest, assez fréquents à ces latitudes, le contrarient parfois, mais il devient plus violent, comme si le barrage momentané, que lui avait opposé le vent, avait accumulé ses eaux, qui se déchargent ensuite. Il crée une mer dangereuse, surtout au bard Sud-Est du Banc des Aiguilles. Sur le banc lui-même, par profondeurs inférieures à 120 mètres, la mer est beaucoup moins forte. Le courant suit plutôt les contours du banc sans les dépasser côté terre. Une faible partie passe sur l'extrémité Sud du banc, ou la contourne, pour rejoindre, au delà du Cap de Bonne-Espérance, le courant de la côte Ouest d'Afrique australe, qui se dirige vers le Nord. Les eaux chaudes atteignent rarement la Baie de la Table (Le Cap), où l'eau est beaucoup plus froide que dans la Baie Simons.

La partie principale du courant des Aiguilles se dirige vers le Sud jusqu'au parallèle de 40° Sud, où elle s'infléchit vers l'Est pour rejoindre le courant de l'Océan Austral, qui vient du Sud-Ouest et de l'Ouest-Sud-Ouest.

La rencontre des eaux chaudes et salées du courant des Aiguilles avec les eaux froides et moins salées du courant de l'Océan Austral crée, entre les parallèles de 37° et 40° Sud, une région de courants variables et de remous, où la température et la salinité varient rapidement q'un point à un autre : des différences de 10°C de température ont été signalées entre points rapprochés. La ligne de réunion des courants est indiquée par un changement de couleur de l'eau.

Contre-courants côtiers :

Le courant du Mozambique et surtout le courant des Aiguilles ne sont nettement dirigés vers le Sud-Ouest qu'à une distance de terre d'au moins 3 milles. Plus près du rivage, il se produit des contre-courants portant vers le Nord-Est et vers l'Est, et parfois à terre. Là où les courants de marée sont importants. Dans le voisinage du Cap des Aiguilles existe un contre-courant portant au Nord (c'est à dire à terre) à une vitesse dépassant parfois 1 nœud.

Courant de l'Océan Indien Austral :

Formé par la rencontre du courant chaud des Aiguilles avec le courant plus froid en provenance de l'Ouest-Sud-Ouest, il se dirige vers l'Est et Est-Nord-Est, sa vitesse moyenne est d'environ 1,5 nœud, des vitesses plus fortes, atteignant 3 nœuds, ont été signalées.

Le courant est plus fort et plus septentrional en été qu'en hiver ; on le rencontre vers le Sud jusqu'à la latitude de 50°. Plus à l'Est, la vitesse diminue ; au voisinage des Kerguelen, ce n'est plus qu'une dérive assez lente, d'une dizaine de milles par jour, qui va rejoindre, au Sud de l'Australie, la dérive de l'Océan Pacifique austral.

Courants au Sud Ouest de l'Australie :

Sur la côte occidentale d'Australie, entre le Cap Leeuwin et la Pointe Cloates, le courant porte généralement au Nord-Ouest, à la vitesse de 1 nœud à 1,5 nœud. Ce courant est profondément modifié par le vent. Pendant l'hiver au voisinage de la terre, il est remplacé par un courant vers le Sud.

Courants sub-équatorial et septentrionaux :

Dans la partie septentrionale de l'Océan Indien, les courants présentent une variation saisonnière remarquable. Le mouvement des eaux suit, dans ses grandes lignes, le mouvement des masses d'air, mouvement commandé par les moussons du Nord-Est pendant l'hiver boréal, du Sud-Ouest pendant l'été boréal.

Pendant l'hiver de l'hémisphère Nord, à l'époque de la mousson du Nord-Est, les courants sont dirigés dans la direction de l'Ouest, aussi bien dans la Mer d'Oman que dans le Golfe du Bengale. Le Sri Lanka est complètement baigné au Nord et au Sud par les eaux de ce courant.

Dans le Golfe du Bengale, à la latitude de Madras, le courant s'infléchit vers le Nord et décrit un circuit dans le sens des aiguilles d'une montre. A la sortie du détroit de Malacca, le courant a une vitesse de 2 à 3 nœuds.

Dans la mer d'Oman, la vitesse du courant vers l'Ouest et le Sud-Ouest n'atteint pas un nœud, elle dépasse 2 nœuds dans le Golfe d'Aden, surtout sur le côte d'Arabie (sur la côte de Somalie, on observe souvent un contre-courant portant vers l'Est, d'une vitesse de 1 nœud). En s'infléchissant vers le Sud le long de la côte des Somalis le courant augmente encore de rapidité (J. Rouch a mesuré 84 milles par jour dans une traversée de Guardafui (Ras Asir) à Zanzibar.

Contre-courant équatorial :

Entre ces courants portant vers l'Ouest et le courant Sud-équatorial, on observe un contre-courant équatorial portant à l'Est, dont la limite Nord est l'équateur et la limite Sud le 6ème parallèle environ. La vitesse de ce contre-courant est très variable, assez faible à son point de départ au voisinage de la côte d'Afrique (1 à 1,5 nœud), vers le milieu de l'Océan Indien, alors que le contre-courant passe entre les Maldives et l'archipel des Chagos, la vitesse peut atteindre 3 nœuds.

Pendant l'été de l'hémisphère Nord, c'est la mousson du Sud-Ouest qui est le vent régulier dans l'Océan Indien septentrional. Les courants changent de direction en même temps que les vents. Dans ces conditions, au lieu de porter à l'Ouest et au Sud-Ouest, ils portent à l'Est et au Nord-Est.

Les plus grandes vitesses du courant de mousson d'été se rencontrent le long de la côte des Somalis et autour de Sri Lanka. Le long de la côte des Somalis, la plus grande vitesse a été de 133 milles par jour (soit plus de 5 nœuds). Cette grande vitesse des courants est due à la vitesse de la mousson du Sud-Ouest qui atteint 12 et même 15 mètres par seconde.

A 150 milles dans le Sud de Socotra, le courant est dévié par les faibles profondeurs (entre l'île de Socotra et le Ras Asir). Sur le parallèle du Ras Hafun, le courant porte vers l'Est jusqu'au méridien de Socotra, puis au Sud Est en conservant une vitesse de 4 nœuds. On a même signalé, à 170 milles au Sud de Socotra, un courant Est-Sud-Est de 7 nœuds. Comme dans ces parages la mousson du Sud-Ouest n'est pas déviée ni sa force diminuée, à la rencontre de la mousson et du courant vers le Sud-Est, il existe une zone où la mer est particulièrement agitée (entre 8° et 11° de latitude Nord et 53° et 58° de longitude Est).

Au voisinage de Sri Lanka, la vitesse du courant ne paraît pas dépasser 3,5 nœuds.

Dans le Golfe d'Aden, on observe le long de la côte d'Afrique un contre-courant dirigé vers l'Ouest, si bien que sur cette côte, en toutes saisons le courant est toujours en sens inverse du vent qui souffle sur le Golfe d'Oman.

Les changements de courants ne sont pas simultanés avec les changements de mousson. Dans l'ensemble, les courants vers le Nord-Est et l'Est durent plus longtemps que les courants vers l'Ouest et le Sud-Ouest.

La côte orientale de Sri Lanka et la péninsule indienne sont reliées par un ensemble d'îles et de récifs coralliens formant le Pont d'Adam, cette topographie permettant d'observer avec précision les changements saisonniers du courant. Entre une de ces îles, l'île Ramesvaran, et la côte indienne, il existe une passe profonde de 3 à 4 mètres et large de 25 à 60 mètres où le courant change de sens avec la mousson, vers le Sud avec la mousson du Nord-Est, vers le Nord avec la mousson du Sud-Ouest. Quand la mousson est bien établie, la vitesse de ce courant atteint 7 nœuds.

Le Golfe Arabe :

Dans le Golfe Arabe, où l'amplitude de la marée est relativement forte et les profondeurs faibles, ce sont les courants de marée qui dominent ; leur vitesse atteint 3 nœuds en plusieurs points. En été, la mousson du Sud-Ouest pousse les eaux à l'intérieur du Golfe ; en hiver, pendant la mousson du Nord-Est, il se produit un mouvement inverse.

Références :

J. Rouch, Traité d'Océanographie physique. Les mouvements de la mer. Vol. 3. Edit. Payot, Paris, 1948.

National Geographic Society, Washington D.C., 1981, pp.228-229

Atlas of Pilot Charts http://msi.nga.mil/NGAPortal/MSI.portal?_nfpb=true&_pageLabel=msi_portal_page_62&pubCode=0003 NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY (USA)

The Red Sea contained 111 species of which the majority are originally from the Indo-Pacific region (Sewell, 1948, p.435). With 280 species this number is still one of the lowest, due in part to the restricted opening into the Indian Ocean, but probably also to the limited number of sampling cruises. Analysis shows that 229 species are shared with the Indian Ocean, and 217 with the Mediterranean. 239 of these relatively cosmopolitan species are also found in several other zones.

Courants en mer Rouge :

En faisant abstraction des courants de marée, sensibles surtout aux extrémités Nord et Sud de la mer Rouge, à savoir dans le Golfe de Suez et dans le détroit de Bab-el-Mandeb, les courants dépendent des moussons de l'Océan Indien.

D'octobre à mars (période de la mousson du Nord-Est) le courant porte au Nord-Nord-Ouest dans le détroit de Bab-el-Mandeb, où il atteint une vitesse de 1 à 2 nœuds, et ce courant peut se faire sentir parfois jusqu'au Nord de la Mer Rouge.

De juin à septembre (période de la mousson du Sud-Ouest) le courant est Sud-Sud-Est du milieu de la mer Rouge jusqu'au détroit de Bab-el-mandeb, où sa vitesse est de 30 à 40 milles par jour. Dans le Nord de la Mer Rouge, on continue souvent à observer dans cette saison un courant vers le Nord-Nord-Ouest.

Références :

J. Rouch, Traité d'Océanographie physique. Les mouvements de la mer. Vol. 3. Edit. Payot, Paris, 1948.

National Geographic Society, Washington D.C., 1981, pp.228-229

Atlas of Pilot Charts http://msi.nga.mil/NGAPortal/MSI.portal?_nfpb=true&_pageLabel=msi_portal_page_62&pubCode=0003 NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY (USA)

Zones: G. of Thailand, Indo-Malay Archipelago (17)  ; China Seas (21) ; China Seas (21)

|

17 |

21 |

Total species: |

649 (25.3 %) (+ 8 ind.) |

641 (25 %) (+ 6 ind.) |

Calanoida: |

531 |

490 |

other orders |

118 |

151 |

Copepoda have not been intensively studied in the Indo-Malay Archipelago since the work of A. Scott (1909) who recorded 326 species (not including Lichomolgidae). Vervoort (1946) et Wilson (1950) contributed to knowledge of the fauna of this region. In view of the large number of islands of all sizes and the deeps that separate them, the total number of species in this zone has probably been vastly underestimated. 380 species, i.e. 57.9 %, are shared with tropical and subtropical zones in the Pacific.

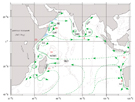

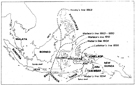

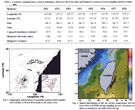

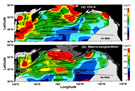

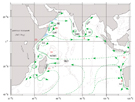

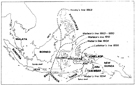

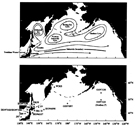

Issued from : A. Fleminger in UNESCO Techn. papers mar. Sci., 1986, 49. [p.89, Fig.5]. Issued from : A. Fleminger in UNESCO Techn. papers mar. Sci., 1986, 49. [p.89, Fig.5].

Sea surface temperature isotherms, °C, surface currents (slender arrows) and Northeast Trade Winds (thick arrows) in eastern Indo-Australian region.

Top two panels show conditions in southern hemisphere winter and summer conditions in the present time and hypothetized for past interglacial stages.

Bottom two panels show conditions thought to prevail during Pleistocene glacial stages. Oblique line shading show areas in which unusually cool (<21°C) surface temperatures may have predominated seasonally and acted as a barrier to the passage of mixed layer stenotherms; land area extended to 200 m isobath to approximately lowered eustatic sea level during glacial stages (modified from Webster & Streten, 1972; Brinton, 1975).

Nota : Dotted shading in the area of Wallacea represents special local conditions that would have lowered surface temperatures on a seasonal basis. Quinn (1971) argues for increased upwelling in equatorial latitudes of the westernmost Pacific during Pleistocene glacial stages. He notes the existence of fossil guano deposits on equatorial islands lying west of the Gilberts Islands, which indicates the past presence of large colonies of sea birds on islands now lacking such colonies.

Presumably during Pleistocene glacial periods, equatorial upwelling in the west Pacific provided the ressources to support the now extinct bird colonies. In general over the past 75000 years, fluctuations in the intensity of the trade winds has been concurrent or preceded fluctuations in the amount of ice stored on continents and wind velocityn of the winter trades intensified during cool climatic stages of the earth and diminished during warm stages (Molina-Cruz, 1977).

Pleistocene glacial stages appear to have persisted for periods of tens of thousands of years.

Bé & Dupless (1976) indicates that the glacial stages persisted for tens of thousands of years several times during the million years of the Pleistocene. For stenothermal species ranging years (1976) show that the half-million –year records for the western Indian Ocean and the quarter-million-year record for te eastern Indian Ocean had cold conditions prevailing for more than half of their respective periods. Van Andel & al. (1967) and Webster & Streten (1972) believe that cool water entered the Timor Sea during Pleistocene glacial stages based on an intensification of the cool, west Australian boundary current an dits more northward penetration. Changes in current intensity during Pleistocene glacial stages have been recorded off South Africa (Hutson, 1980).

In the northern hemisphere during Pleistocene glacial winters, the NE Trades probably intensified sufficiently to induce coastal upwelling off northwest New Guinea and the eastern Moluccas. Webster & Streten (1972) suggest that surface temperatures off northwest New Guinea ranged from 22 to 24°C, while the CLIMAP Project (1976) indicates 25 to 27°C in the southern hemisphere winter for this area. Reducing these values by 3°C, the extent surface temperatures are lowered in upwelling plumes off New Guinea, would depress winter Pleistocene surface temperatures to a range of 19 to 24°C, i .e., well below present-day winter conditions. Assuming that the median, 21.5°C, is close to actual surface temperatures in upwelling plumes of the Pleistocene glacial winter, the northern end of Wallacea would be inhospitable to tropical stenotherms roughly from October to March. In the southern hemisphere's winter, the West Australia Boundary Current would intensify and the SE Trades might cause coastal upwelling along the Sehul shelf. It is reasonable to expect winter surface temperatures of about 20°C in the Timor and Banda Seas (as shown by Webster & Srreten, 1972), rendering the southern end of Wallacea inhospitable to surface-bound stenotherms roughly between April and September.

The hypothetized glacial-stage conditions shown in the lower two panels of figure 5 would enhance C. philippinensis and Rhincalanus nasutus population expansions, while depressing populations of sternothermal pontellids.

Stratigraphic evidence by Bé & Duplessy (1976) indicates that the glacial stages persisted for tens of thousands of years several times during the million years of the Pleistocene. For stenothermal species ranging across Wallacea, each glacial sequence would interrupt their distribution and provide an opportunity for the allopartic subpopulations to diverge.

If Wallacea was a long-term barrier to passage of stenothermal species of the mixed layer, we should expert to see evidence of its vicariant role in speciation patterns of locally distributed species groups. That is, sister species may be expected to have allopatric or parpatric distributions extending from Wallacea.

Biogeographic bounderies proposed for separating the Oriental and the Australia/New Guinea faunal regions (see George, 1981). Biogeographic bounderies proposed for separating the Oriental and the Australia/New Guinea faunal regions (see George, 1981).

Issued from : A. Fleminger in UNESCO techn. Pap.Mar. Sci., 1986, 49. [p.84, Fig.1].

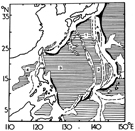

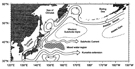

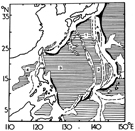

Topographic feature of the Kuroshio region (modified from Mogi, 1972). Topographic feature of the Kuroshio region (modified from Mogi, 1972).

Ridges: A, Izu-Ogasawara; B, Mariana; C, Yap; D, Kyushu-Palau; E, Daito, F, Ryukyu.

Basins: 1, Shikoku; 2, West Mariana; 3, Philippines; 4, South China Sea.

Others: I, Okinawa Trough; II Bashi Channel; III, Sakishima Depression; IV, Tokara Strait.

Issued from : J.L Su, B.X. Guan & J.Z. Jiang in Ann. Rev., 1990, 28. [p.13, Fig.2].

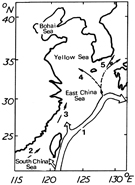

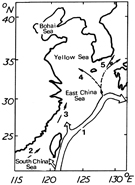

Schematic picture of the Kuroshio Current and its branches in the China Seas: 1, Kuroshio Current; 2, South China Sea Warm Current; 3, Taiwan Warm Current; 4, Yellow Sea Warm Current; 5, Tsushima Current. Schematic picture of the Kuroshio Current and its branches in the China Seas: 1, Kuroshio Current; 2, South China Sea Warm Current; 3, Taiwan Warm Current; 4, Yellow Sea Warm Current; 5, Tsushima Current.

Issued from : J.L Su, B.X. Guan & J.Z. Jiang in Ann. Rev., 1990, 28. [p.37, Fig.22].

Issued from : M.-C. Jang, S.H. Baek, P.-G. Jang, W.-J. Lee & K. Shin in Ocean and Polar Res., 2012, 34 (1). [p.40, Fig.2]. Issued from : M.-C. Jang, S.H. Baek, P.-G. Jang, W.-J. Lee & K. Shin in Ocean and Polar Res., 2012, 34 (1). [p.40, Fig.2].

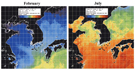

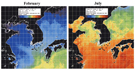

Weekly average sea surface temperature (SST) derived from NOAA/AVHRR during periods in February and July 2009 in the Korea Strait.

Sampling stations are marked as circles.

Issued from : L.-C. Tseng, R. Kumar, H.-U. Dahms, Q.-C. Chen & J.-S. Hwanh in Zool. Studies, 2008, 47 (1). [p.53, Fig.4]. Issued from : L.-C. Tseng, R. Kumar, H.-U. Dahms, Q.-C. Chen & J.-S. Hwanh in Zool. Studies, 2008, 47 (1). [p.53, Fig.4].

Monthly average sea-surface temperatures (SSTs) derived from averaged hourly recordings (AVHRRs) for (A) Aug. 1998, (B) Dec. 1998, (C) Mar. 1999, and (D) May 1999.

Nota: The Taiwan Strait is a relatively shallow (with an average depth of 60 m), 350 km long, and 180 km wide channel between the island of Taiwan and the southeastern Chinese coast, connecting the two marginal seas of the western Pacific, the East China Sea and the South China Sea.

In the Taiwan Strait there is a congruence of 3 different water masses (East China Sea, South China Sea), and the water masses representing the Kuroshio Current of the western North Pacific such hydrographic conditions affect the zooplankton community composition in the Taiwan Strait..

Wind patterns in this region are determined by the typical East Asian monsoon that is from the northeast (NE) during winter (Oct.-Mar.) and from southwest (SW) during summer (May-Aug.).

During the NE monsoon the China Coastal Current with low temperatures, low salinities, and high nutrient levels moves southwards driving zooplankton from the Bohai Sea, the Yellow Sea, and the East China Sea towards the Taiwan Strait.

Throughout the year, the warm, highly saline, and nutrient-poor Kuroshio Branch Current intrudes into the Taiwan Strait through the northern South China Sea and along the coast of southwestern Taiwan. However, during the prevailing NE monsoon period , the southherly flowing China Coastal Current near the Penghu Channel, south of the Changyun Ridge in the southeastern Taiwan Strait.

In spring when the NE monsoon weakens the Kuroshio Branch Current moves northward along the local isobaths into the northern part of the Taiwan Strait. Conversely, under the prevailing winds of the SW monsoon (May-Aug.), the South China Sea Warm Current with intermediate temperatures, salinities, and nutrient levels intrudes into the Taiwan Strait and moves northward together with the Kuroshio Branch Current that transports plankton from the northern South China Sea.

The hydrographic properties of this part (NW Taiwan) of the Taiwan Strait are mainly influenced by the NE and SW monsoons. The influence of cold water masses disappears during summer with increasing strength of the SW monsoon as water masses from the northern part of the South China Sea enter the Taiwan Strait and influence the hydrography around the west coast of Taiwan, and Guangdong and Fujian Provinces, China.

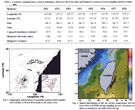

Issued from : Y.-C. Lan, M.-A. Lee, C.-H. Liao & K.-T. Lee in J. Mar. Sci. Techn., 2009, 17 (1). [p.2, Table 1, Figs. 1, 2]. Issued from : Y.-C. Lan, M.-A. Lee, C.-H. Liao & K.-T. Lee in J. Mar. Sci. Techn., 2009, 17 (1). [p.2, Table 1, Figs. 1, 2].

Copepod community structure of the winter frontal zone induced by the Kuroshio branch current and the China coastal current in the Taiwan Strait.

Nota: Copepods collected with a Bongo plankton net (mesh aperture: 335 µm), towed obliquely.

At each station, temperature and salinity at different depths were obtained by CTD profiler from the sea surface to a depth near the bottom. NOAA satellites provide SST measurements showing the spatial distribution of surface temperature with 1.1 km spatial resolution.

Chen, B (1986) records 345 species in the China Seas from the Bohai Sea and the Yellow Sea at 40° N to the eastern and southern tropical China Seas .

Zhang, W (2007) divides the China Seas into four sub-areas (South China Sea, East China Sea, Yellow Sea and Bohai Sea) ( See the interactive distribution map  ). Concerning the division position of the sub-areas, in China, the line connecting Cheju Island and north bank of Yangtze River is the division line of Yellow Sea and East China Sea. The line connecting Nanao Island of Guangdong Province and Eluanbi of Taiwan Island is the division line of the East China Sea and South China Sea. About the ascription of sea east of Taiwan Island Zhang proposes that this area should be included into South China Sea due to the oceanic water properties. ). Concerning the division position of the sub-areas, in China, the line connecting Cheju Island and north bank of Yangtze River is the division line of Yellow Sea and East China Sea. The line connecting Nanao Island of Guangdong Province and Eluanbi of Taiwan Island is the division line of the East China Sea and South China Sea. About the ascription of sea east of Taiwan Island Zhang proposes that this area should be included into South China Sea due to the oceanic water properties.

The limits, however, are somewhat artificial, not taking into account movement of masses of water in time and space, and some species are so redundant with those of southern Japan (zone 22) and northern Malaysia and west of the Philippines (zone 17).

Courants dans les mers de Chine :

Les courants dans les mers de Chine sont principalement des courants de mousson.

En mousson du Nord-Est ou de Nord, d'octobre à mars, les courants portent vers le Sud et le Sud-Ouest.

En mousson de Sud-Ouest et de Sud, de juin à août, les courants portent au Nord et au Nord-Est.

Pendant les saisons intermédiaires, avril-mai d'une part, septembre et début octobre d'autre part, les courants sont plus irréguliers et variables.

La vitesse de ces courants de mousson peut dépasser 1 nœud, surtout au voisinage des côtes. Elle atteint près de 3 nœuds en mousson de Sud-Ouest dans le Détroit de Taiwan.

Dans la partie orientale de la Mer de Chine septentrionale, entre Taiwan et le Japon, le Kuroshio passe au travers des îles Ryukyu et se fait sentir à l'ouest de ces îles. Sa vitesse atteint 3 nœuds ; ses eaux chaudes et bleu foncé sont nettement différentes des eaux côtières de plusieurs degrés plus froides, de couleur vert jaunâtre, et qui, pendant l'hiver, coulent en sens contraire.

Références :

J. Rouch, Traité d'Océanographie physique. Les mouvements de la mer. Vol. 3. Edit. Payot, Paris, 1948.

National Geographic Society, Washington D.C., 1981

Atlas of Pilot Charts http://msi.nga.mil/NGAPortal/MSI.portal?_nfpb=true&_pageLabel=msi_portal_page_62&pubCode=0003 NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY (USA)

Zones: Japan (22)  ; NW North Pacific (23) ; NW North Pacific (23)

|

22 |

23 |

Total species: |

711 (27.7 %) (+ 8 ind.) |

368 (14.3 %) (+ 2 ind.) |

Calanoida: |

556 |

305 |

other orders |

155 |

63 |

Warm and cold currents around Japan and fishing grounds for pelagic fish, such as skipjack, tuna and squid. Warm and cold currents around Japan and fishing grounds for pelagic fish, such as skipjack, tuna and squid.

A schematic expression of horizontal structures of SST, with fishing grounds in and around the WCR (warm-core rings). A-H are the active areas where the WCRs are often produced.

Issued from : T. Sugimoto & H. Tameishi in Deep-Sea Res., 39, suppl. 1, 1992. [p.S186, Fig.1 (b)].

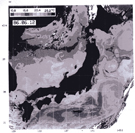

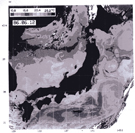

A satellite thermal image of SST around Japan, obtained by the NOAA/AVHRR on 12 June 1986. A satellite thermal image of SST around Japan, obtained by the NOAA/AVHRR on 12 June 1986.

Issued from : T. Sugimoto & H. Tameishi in Deep-Sea Res., 39, suppl. 1, 1992. [p.S186, Fig.1 (a)].

The bottom topography and geographical locations for the Japan/East Sea. The depth contours are at 300 and 1000 m. The bottom topography and geographical locations for the Japan/East Sea. The depth contours are at 300 and 1000 m.

Issued from : D.-K. Lee & P.P. Niiler in Deep-Sea Res. II, 52, 2005. [p.1548, Fig.1].

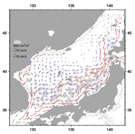

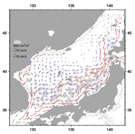

Schematic map of the surface currents in the Japan/East Sea based on Lee and Niiler's (2005) drifter observations. Dotted paths (Tsushima Warm Current [TWC] and North Korean Cold Current [NKCC]) represent the currents observed only during spring and summer, and solid paths (East Korean Warm Current

[EKWC] and East Sea Current) represent the currents observed all the year. Schematic map of the surface currents in the Japan/East Sea based on Lee and Niiler's (2005) drifter observations. Dotted paths (Tsushima Warm Current [TWC] and North Korean Cold Current [NKCC]) represent the currents observed only during spring and summer, and solid paths (East Korean Warm Current

[EKWC] and East Sea Current) represent the currents observed all the year.

Issued from : D.-K. Lee & P.P. Niiler in Deep-Sea Res. I, 57, 2010. [p.1223, Fig.1].

Mean velocity and variance ellipses on 0.5° x 0.5° bins. Red vectors are for the mean speed larger than 10 cm/s and blue vectors are those smaller than 10 cm/s. Mean velocity and variance ellipses on 0.5° x 0.5° bins. Red vectors are for the mean speed larger than 10 cm/s and blue vectors are those smaller than 10 cm/s.

Issued from : D.-K. Lee & P.P. Niiler in Deep-Sea Res. II, 52, 2005. [p.1550, Fig.3].

The schematic patterns of surface circulation from

drifter observation drawn on 100 m mean temperature from JMA (2001) [In Oceanographic Normals and Analysis for the period 1971–2000 (CD-ROM). Japan Meteorological Agency, Tokyo]. Red vectors are for mean current larger than 10 cm/s. The schematic patterns of surface circulation from

drifter observation drawn on 100 m mean temperature from JMA (2001) [In Oceanographic Normals and Analysis for the period 1971–2000 (CD-ROM). Japan Meteorological Agency, Tokyo]. Red vectors are for mean current larger than 10 cm/s.

Issued from : D.-K. Lee & P.P. Niiler in Deep-Sea Res. II, 52, 2005. [p.1560, Fig.16].

Bathymetry of the Japan Sea (a) and numbers show the water depth in meters.In (b) schematic map for sea surface currents (after Senjyu, 1999) with abbrevations: TWC = the Tsushima Warm Current; LC = the Liman Current; EKWC = the East Korean Warm Current; NKCC = the North Korean Cold Current; Bathymetry of the Japan Sea (a) and numbers show the water depth in meters.In (b) schematic map for sea surface currents (after Senjyu, 1999) with abbrevations: TWC = the Tsushima Warm Current; LC = the Liman Current; EKWC = the East Korean Warm Current; NKCC = the North Korean Cold Current;

OI : the Oki Island and NP : Noto Peninsula.

Issued from : A. Morimoto & T. Yanagi in J. Oceanogr., 2001, 57. [p.2, Fig.1].

Issued from : M.-C. Jang, S.H. Baek, P.-G. Jang, W.-J. Lee & K. Shin in Ocean and Polar Res., 2012, 34 (1). [p.40, Fig.2]. Issued from : M.-C. Jang, S.H. Baek, P.-G. Jang, W.-J. Lee & K. Shin in Ocean and Polar Res., 2012, 34 (1). [p.40, Fig.2].

Weekly average sea surface temperature (SST) derived from NOAA/AVHRR during periods in February and July 2009 in the Korea Strait.

Sampling stations are marked as circles.

Issued from : L.-C. Tseng, R. Kumar, H.-U. Dahms, Q.-C. Chen & J.-S. Hwanh in Zool. Studies, 2008, 47 (1). [p.53, Fig.4]. Issued from : L.-C. Tseng, R. Kumar, H.-U. Dahms, Q.-C. Chen & J.-S. Hwanh in Zool. Studies, 2008, 47 (1). [p.53, Fig.4].

Monthly average sea-surface temperatures (SSTs) derived from averaged hourly recordings (AVHRRs) for (A) Aug. 1998, (B) Dec. 1998, (C) Mar. 1999, and (D) May 1999.

Nota: The Taiwan Strait is a relatively shallow (with an average depth of 60 m), 350 km long, and 180 km wide channel between the island of Taiwan and the southeastern Chinese coast, connecting the two marginal seas of the western Pacific, the East China Sea and the South China Sea.

In the Taiwan Strait there is a congruence of 3 different water masses (East China Sea, South China Sea), and the water masses representing the Kuroshio Current of the western North Pacific. Such hydrographic conditions affect the zooplankton community composition in the Taiwan Strait.

Wind patterns in this region are determined by the typical East Asian monsoon that is from the northeast (NE) during winter (Oct.-Mar.) and from southwest (SW) during summer (May-Aug.).

During the NE monsoon the China Coastal Current with low temperatures, low salinities, and high nutrient levels moves southwards driving zooplankton from the Bohai Sea, the Yellow Sea, and the East China Sea towards the Taiwan Strait.

Throughout the year, the warm, highly saline, and nutrient-poor Kuroshio Branch Current intrudes into the Taiwan Strait through the northern South China Sea and along the coast of southwestern Taiwan. However, during the prevailing NE monsoon period, the southherly flowing China Coastal Current near the Penghu Channel, south of the Changyun Ridge in the southeastern Taiwan Strait.

In spring when the NE monsoon weakens the Kuroshio Branch Current moves northward along the local isobaths into the northern part of the Taiwan Strait. Conversely, under the prevailing winds of the SW monsoon (May-Aug.), the South China Sea Warm Current with intermediate temperatures, salinities, and nutrient levels intrudes into the Taiwan Strait and moves northward together with the Kuroshio Branch Current that transports plankton from the northern South China Sea.

The hydrographic properties of this part (NW Taiwan) of the Taiwan Strait are mainly influenced by the NE and SW monsoons. The influence of cold water masses disappears during summer with increasing strength of the SW monsoon as water masses from the northern part of the South China Sea enter the Taiwan Strait and influence the fhydrography around the west coast of Taiwan, and Guangdong and Fujian Provinces, China.

Le Courant du Japon ou Kuroshio :

La branche du courant équatorial Nord qui remonte vers le Nord-Ouest atteint Taiwan, et à partir de là, le courant du Japon prend une individualité nette.

A la hauteur de Taiwan, le Kuroshio a une largeur de 100 milles et une vitesse de 1,5 nœud. Plus au Nord, le long des îles Ryukyu, sa largeur diminue jusqu'à une soixantaine de milles ; sa vitesse est alors de 2 à 3 nœuds dans l'axe, de 1 nœud sur les bords. Par 32° Nord, devant l'île Kyushu, le Kuroshio n'a pas une vitesse supérieure à 2 nœuds. Au Cap Moroto Saki, au delà duquel la côte du Japon tourne brusquement au Nord, le courant a une largeur de 50 milles ; sa vitesse, de 2 nœuds en moyenne, peut atteindre parfois 5 nœuds. Le courant s'oriente alors vers l'Est, pour se souder à la dérive vers l'Est du Pacifique Nord.

En hiver, les eaux de surface du Kuroshio ont une température d'environ 24° à la hauteur de Taiwan ; cette température décroît à mesure qu'on s'avance vers le Nord, et n'est plus que de 13°C environ par 35° de latitude. En été, ces températures sont respectivement de 27° et de 18°C environ ; c'est seulement en cette saison que les eaux du Kuroshio sont nettement plus chaudes que les eaux du large. Tout le long de son parcours, le Kuroshio a une salinité de 34,5. Ses eaux sont bleu foncé (nom qui en japonais veut dire courant noir).

Courant de la Mer du Japon :

Une branche du Kuroshio pénètre dans la Mer du Japon par le détroit de Corée (appelé aussi Courant de Tu Sima) ; il a une vitesse moyenne de 1,5 nœud, plus fort en été, où sa vitesse dépasse 2,5 nœuds. Le courant s'oriente vers le Nord-Est dans la Mer du Japon, longe les côtes japonaises à une vitesse de 10 milles par jour, et atteint le Golfe de Tartarie. Sur la côte d'Asie, il existe un courant vers le Sud, plus marqué en hiver qu'en été.

Dans les détroits de Tsugaru et de La Pérouse, le courant porte à l'Est, souvent à des vitesses très grandes, atteignant 6 à 7 nœuds.

Courant Oyashio :

Un courant froid venant de la Mer de Béring, l'Oyashio, descend à une vitesse de plus d'un nœud le long des Kouriles et jusqu'au rivage de Honshu, où il crée, par contraste avec le Kuroshio qui s'étale plus au large, une sorte de zone de contact. Ce courant n'atteint jamais les abords du Golfe de Tokyo, les anomalies négatives de température qu'on y observe en hiver sont dues à des remontées d'eaux froides, ou à l'influence des basses températures qui règnent alors au Japon.

Références :

J. Rouch, Traité d'Océanographie physique. Les mouvements de la mer. Vol. 3. Edit. Payot, Paris, 1948.

National Geographic Society, Washington D.C., 1981

Atlas of Pilot Charts http://msi.nga.mil/NGAPortal/MSI.portal?_nfpb=true&_pageLabel=msi_portal_page_62&pubCode=0003 NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY (USA)

Schematic diagram for the transport of the fresh Oyashio water (black arrowed curves) and old NPIW (North Pacific Intermediate Water) (gray arrowed curves) in the salinity minimum layer. Schematic diagram for the transport of the fresh Oyashio water (black arrowed curves) and old NPIW (North Pacific Intermediate Water) (gray arrowed curves) in the salinity minimum layer.

The movement and mixing of these waters were strongly related to the small and meso scales features in the MWR (Mixed Water Region) such as the First Branch of the Oyashio (FBO), the Second Branch of the Oyashio (SBO), the inner cold belt (ICB), warm core ring (WCR) and warm streamer (WS).

Old NPIW transported by the Kuroshio Extension (KE) strongly mixed with the fresh Oyashio water extended from the first branch of the Oyashio (FBO) in and around WS.

The fresh Oyashio water extended from SBO was transported eastward along the northern edge of KE beyond 150°E with a form of rather narrow band.

The subsurface intrusion at the northern edge of KE ejected lens-like Oyashio waters southward across KE axis and split northwarde into a warm core ring probably by the interaction of KE and WCR, suggesting the processes of freshening NPIW in the offshore MWR and the Kuroshio recirculation region.

The aim is to understand the actual formation process of the North Pacific Intermediate Water examined on the basis of a synoptic CTD observation carried out in May-June 1992.

Issued from : K. Okuda, I. Yasuda, Hiroe Y. & Y. Shipmizu in J. Oceanogr., 2001, 57. [p.138, Fig.10].

233 species are common to Japan and the sub-Arctic zone (i.e. 32.5 %), although the dominant influence on Japanese planktonic fauna is generally tropical.

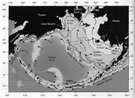

Diagram of the relationship of the Oyashio Current to other currents in the northwest Pacific Ocean (Modified from Qiu, 2001).

Diagram of the relationship of the Oyashio Current to other currents in the northwest Pacific Ocean (Modified from Qiu, 2001).

Issued from : Y. Sakurai in Deep-Sea Research II, 2007, 54; [p.2527, Fig.1].

Of 171 species common to the NW and NE Pacific sub-Arctic zones, 11 are known only in these two zones.

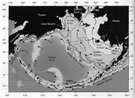

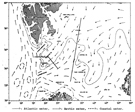

Schematic current systems (top, redrawn from Favorite & al., 1976) and sampling stations in the subarctic Pacific Ocean and neighboring waters (bottom). Schematic current systems (top, redrawn from Favorite & al., 1976) and sampling stations in the subarctic Pacific Ocean and neighboring waters (bottom).

Issued from : T. Kobari & T. Ikeda in J. Plankton Res., 2001, 23 (3). [p.288, Fig.1].

The Bering Sea. Isobaths shown are 50 m (between inner and middle domains), 100 m (between middle and outer domains) and 200 m (between outer domain and slope/basdin. Schematic of major currents based on Stabeno & al. (1999). AC: Anadyr Current; ACC: Alaska Coastal Current; ANSC: Aleutian North Slope Current; BS: Bering Strait. The Bering Sea. Isobaths shown are 50 m (between inner and middle domains), 100 m (between middle and outer domains) and 200 m (between outer domain and slope/basdin. Schematic of major currents based on Stabeno & al. (1999). AC: Anadyr Current; ACC: Alaska Coastal Current; ANSC: Aleutian North Slope Current; BS: Bering Strait.

Issued from : K. Aydin & F. Mueter in Deep-Sea Research II, 2007, 54. [p.2502, Fig.1].

Map of the northern Bering Sea and Chukchi. Map of the northern Bering Sea and Chukchi.

The box marks the survey area of the hydrographic conditions (temperature, salinity and chlorophyll) and Gray whale counts during June to September. The arrows show the prevailing current regime.

Issued from : B.A. Bluhm, K.O. Coyle, B. Konar & R. Highsmith in Deep-Sea Resaeach, 2007, 54. [p.2921, Fig.1]. .

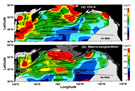

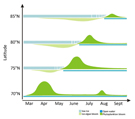

Average summer season distributions of upper ocean chlorophyll concentration (upper panel) and zooplankton biomass (lower panel) in the subarctic Pacific, overlaid with circulation pattern. Figure courtesy of K. Tadokoro, modified by colorization and addition of circulation streamlines from Sugimoto and Tadokoro, 1997. Average summer season distributions of upper ocean chlorophyll concentration (upper panel) and zooplankton biomass (lower panel) in the subarctic Pacific, overlaid with circulation pattern. Figure courtesy of K. Tadokoro, modified by colorization and addition of circulation streamlines from Sugimoto and Tadokoro, 1997.

Issued from : Mackas D.L. & Tsuda A., 1999. - Mesozooplankton in the eastern and western subarctic Pacific: community structure, seasonal life histories, and interannual variability. Progress in Oceanography, 43. [p.352, Fig.8].

Map of the subarctic Pacific showing place names referred to in this paper (adapted from Brodeur et al., 1996). Map of the subarctic Pacific showing place names referred to in this paper (adapted from Brodeur et al., 1996).

Issued from : Mackas D.L. & Tsuda A., 1999. - Mesozooplankton in the eastern and western subarctic Pacific: community structure, seasonal life histories, and interannual variability. Progress in Oceanography, 43. [p.337, Fig.1].

Major topographic features of the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands. Contours of 100, 200, 1000 and 3500 m are shown. (Basic map from U.S. GLOBEC 1996). Major topographic features of the Bering Sea and Aleutian Islands. Contours of 100, 200, 1000 and 3500 m are shown. (Basic map from U.S. GLOBEC 1996).

Issued from : Takahashi K., 1998. - The Bering and Okhotsk Seas: modern and past

paleoceanographic changes and gateway impact. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 16 (1). [p.50, Fig.1].

A map showing surface currents in the Bering Sea (from Arsen'ev 1967). A map showing surface currents in the Bering Sea (from Arsen'ev 1967).

Issued from : Takahashi K., 1998. - The Bering and Okhotsk Seas: modern and past

paleoceanographic changes and gateway impact. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 16 (1). [p.51, Fig.2].

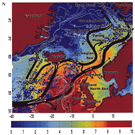

Surface thermal fronts of the Okhotsk Sea from Pathfinder data, 1985–1996. Surface thermal fronts of the Okhotsk Sea from Pathfinder data, 1985–1996.

Issued from : Belkin I.M. & Cornillon P.C., 2004. - Surface Thermal Fronts of the Okhotsk Sea. Physical Oceanography, 2 (1-2). [p.9, Fig.1].

Major topographic features of the Okhotsk Sea and Kuril Islands. Contours of 100, 200, 500, 1000, 2000, 2500

and 3000 m are shown (modified from Gnibidenko and Khvedchuk 1982). Major topographic features of the Okhotsk Sea and Kuril Islands. Contours of 100, 200, 500, 1000, 2000, 2500

and 3000 m are shown (modified from Gnibidenko and Khvedchuk 1982).

Issued from : Takahashi K., 1998. - The Bering and Okhotsk Seas: modern and past

paleoceanographic changes and gateway impact. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 16 (1). [p.52, Fig.3].

A map sho wing surface currents in the Okhotsk Sea and adjacent regions. Note that a part of the Kamchatka

Current enters into the Okhotsk Sea and a part of the Okhotsk Gyre water exits from the Sea to the Paci®c to form the Oyashio Current just south of the Kuril Islands. The Okhotsk Sea circulation is compiled by R. Tiedemann, employing data obtained by Dodimead et al. (1963), Sancetta (1981), and Talley (1991). A map sho wing surface currents in the Okhotsk Sea and adjacent regions. Note that a part of the Kamchatka

Current enters into the Okhotsk Sea and a part of the Okhotsk Gyre water exits from the Sea to the Paci®c to form the Oyashio Current just south of the Kuril Islands. The Okhotsk Sea circulation is compiled by R. Tiedemann, employing data obtained by Dodimead et al. (1963), Sancetta (1981), and Talley (1991).

Issued from : Takahashi K., 1998. - The Bering and Okhotsk Seas: modern and past

paleoceanographic changes and gateway impact. Journal of Asian Earth Sciences, 16 (1). [p.53, Fig.4].

Courant du Kamtchatka :

Ce courant froid en provenance de la mer de Béring s'écoule le long de la côte Est de la presqu'île du Kamtchatka et des îles Kouriles jusqu'à Hokkaido où il se fond avec l'Oyashio.

Courants de la Mer d'Okhotsk :

Le mouvement général des courants est dans le sens anticyclonique, ceux-ci suivant les côtes.

Sur la côte Nord, on trouve un courant vers l'Ouest ; sur la côte Ouest et auprès de l'île Sakhaline, un courant vers le Sud ; le long de la côte du Kamtchatka, un courant vers le Nord. Les courants vers le Sud sont dans l'ensemble prépondérants ; ils sont faibles, atteignant à peine une vitesse d'un demi nœud, et souvent profondément modifiés par les courants de marée, dont la composante diurne a une forte amplitude : à l'entrée du golfe de Penjina, ces courants de marée atteignent des vitesses de 6 à 7 nœuds. Dans les chenaux qui séparent les îles Kouriles, les courants, fortement influencés par les marées, sont très rapides (des vitesses supérieures à 6 nœuds ont souvent été observées).

D'une façon générale, les courants portent vers le Sud et apportent les eaux froides de la Mer d'Okhotsk à l'Oyashio.

Références :

J. Rouch, Traité d'Océanographie physique. Les mouvements de la mer. Vol. 3. Edit. Payot, Paris, 1948.

National Geographic Society, Washington D.C., 1981

Atlas of Pilot Charts http://msi.nga.mil/NGAPortal/MSI.portal?_nfpb=true&_pageLabel=msi_portal_page_62&pubCode=0003 NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY (USA)

Zones: North East Pacific(24)  ; California (25) ; California (25)

|

24 |

25 |

Total species: |

298 (11.6 %) (+ 1 ind.) |

458 (17.9 %) (+ 1 ind.) |

Calanoida: |

231 |

360 |

other orders |

67 |

98 |

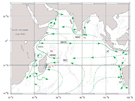

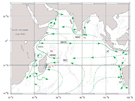

Map of the NE Pacific (adapted from Ware and McFarlane, 1989) showing location of the shelf-slope-offshore transition region (shaded area) and annual-averaged large-scale current patterns (arrows). The coastal transition region includes both the NE Pacific alongshore boundary current systems: the equatorward/upwelling California Current and the poleward/downwelling Alaska Current/Alaska Coastal Current. Although not shown in the annual averages, the boundary currents undergo seasonal variability in speed and direction (generally more poleward/less equatorward in winter, more equatorward/less poleward in summer), and both produce strong mesoscale cross-shore motion in the form of meanders, eddies and filaments. Map of the NE Pacific (adapted from Ware and McFarlane, 1989) showing location of the shelf-slope-offshore transition region (shaded area) and annual-averaged large-scale current patterns (arrows). The coastal transition region includes both the NE Pacific alongshore boundary current systems: the equatorward/upwelling California Current and the poleward/downwelling Alaska Current/Alaska Coastal Current. Although not shown in the annual averages, the boundary currents undergo seasonal variability in speed and direction (generally more poleward/less equatorward in winter, more equatorward/less poleward in summer), and both produce strong mesoscale cross-shore motion in the form of meanders, eddies and filaments.

Issued from : Mackas D.L. & Coyle K.O., 2005. - Shelf-offshore exchanges processes, and their effects on mesozooplankton biomass and community composition patterns in the northeast Pacific. Deep-Sea Res. II , 52. [p.708, Fig.1].

Map of the study area showing bathymetry and approximate summer circulation pattern. Solid arrows indicate near-bottom currents, open arrows show upper layer currents. Map of the study area showing bathymetry and approximate summer circulation pattern. Solid arrows indicate near-bottom currents, open arrows show upper layer currents.

Issued from : Mackas D.L. & Sefton H.A., 1982. - Plankton species assemblages off southern Vancouver Island: Geographic pattern and temporal variability. Journal of Marine Resarch, 40 (4). [p.1176, Fig.1].

The north-eastern Pacific (Aleutians , Gulf of Alaska , "P" Station, British Colombia), sub-Arctic in character, is one of the least diversified regions.

It is, however, also one of the least explored (Wilson, 1942 a, 1950; Davis, 1949) with the exception of "P Station" (50° N, 145° W). In this region, 175 species are shared with the Californian zone (i.e. 58.5 %) and 171 species with the North-west region (i.e. 57.2 %). These percentages confirm the uniqueness of the sub-Arctic community.

The communities of the Californian and Japanese regions have been united in the northern sub-tropical zone (Van der Spoel & Heyman, 1983, p.12, fig.11), which would seem to confirm the percentages of species common to the two zones: 333 common species (i.e. 72.5 %).

Courant de l'Alaska :

La dérive du Pacifique Nord, lorsqu'elle atteint, vers le 50° degré de latitude, les rivages américains, se divise en deux courants. Au Nord, le courant de l'Alaska suit vers le Nord-Ouest la côte de la Colombie Britannique et de l'Alaska à une vitesse qui peut atteindre 1,5 nœud. Il contourne le Golfe d'Alaska, dessinant un circuit dans le sens inverse des aiguilles d'une montre, se renforce à l'Ouest de l'île Kodiak jusqu'aux îles Aléoutiennes les plus orientales. Ces eaux sont plus chaudes que celles plus Sud.

Courant de Californie :

La deuxième branche de la dérive du Pacifique Nord suit vers le Sud la côte de l'Amérique depuis la latitude de 50° Nord jusqu'à la presqu'île de Basse Californie par 23° Nord. C'est un courant froid, large de 200 à 300 milles, dont la vitesse est de ¾ de nœud. Accompagné de remontées d'eaux froides (upwelling), il donne, à l'entrée de la Baie de San Francisco, des températures de la mer qui ne dépassent pas 15°C en plein été.

Le courant suit la direction de la côte vers le Sud-Sud-Est, mais commence à s'incliner vers le Sud et le Sud-Ouest dès la hauteur de Monterey. Il règne alors le long de la côte, surtout en hiver, un contre-courant ou Courant de Davidson.

A la hauteur du Cap San Lucas, extrémité méridionale de la Basse Californie, le courant de Californie est orienté vers le Sud-Ouest et rejoint les eaux du courant équatorial.

Références :

J. Rouch, Traité d'Océanographie physique. Les mouvements de la mer. Vol. 3. Edit. Payot, Paris, 1948.

National Geographic Society, Washington D.C., 1981

Atlas of Pilot Charts http://msi.nga.mil/NGAPortal/MSI.portal?_nfpb=true&_pageLabel=msi_portal_page_62&pubCode=0003 NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY (USA)

Zones: Central Tropical Pacific (19)  ; Eastern Tropical Pacific (20) ; Eastern Tropical Pacific (20)

|

19 |

20 |

Total species: |

541 (21.1 %) (+ 9 ind.) |

514 (20 %) (+ 3 ind.) |

Calanoida: |

433 |

401 |

other orders |

108 |

113 |

352 species species are common to the two regions (i.e. 64.1 % and 68 % respectively).

Zone 19 :

Dans la région comprise entre les tropiques et soumise aux alizés, les eaux de l'Océan Pacifique Nord ont un mouvement général vers l'Ouest. Il se forme ainsi deux courants équatoriaux.

Le courant équatorial du Nord est compris entre les parallèles 20°-25° Nord et 8°-9° Nord. Le courant équatorial Sud entre les parallèles 4°-5 °Nord et 20°-25° Sud.

Les îles Hawaï sont comprises dans le courant équatorial du Nord et Tahiti dans le courant équatorial du Sud, à sa limite Sud.

La vitesse de ces courants équatoriaux varie entre un demi nœud et 3 nœuds ; elle est plus faible à mesure qu'on s'éloigne de l'équateur. Le courant équatorial Sud a une vitesse plus forte que le courant équatorial Nord.

Les deux courants équatoriaux ne se réunissent pas, comme ils le font dans l'Atlantique, mais sont séparés sur tout leur parcours par un contre-courant vers l'Est qui se fait sentir depuis le Sud des Philippines jusqu'à la côte américaine, (en été de l'hémisphère Nord) sur une bande de 300 milles de largeur, entre 4°-5° de latitude Nord et 8°-9° de latitude Nord (en été de l'hémisphère Nord), en hiver sur une bande beaucoup plus étroite, surtout au milieu de l'Océan Pacifique, et plus méridionale. La vitesse du contre-courant est plus faible que celle des courants équatoriaux, elle ne dépasse pas 2 nœuds. Pendant les mois d'hiver de l'hémisphère Nord, il arrive qu'elle soit à peine sensible. Le contre-courant assure, pour une part plus importante que dans l'Atlantique, le retour vers l'Est des eaux transportées par les courants équatoriaux.

La présence d'archipels sur le parcours des courants équatoriaux apporte des modifications, mais toutes locales, à ces courants, qui sont alors divisés et parfois fortement déviés. Des remontées d'eaux profondes (upwelling) se traduisent par une baisse de la température superficielle.

Dans la partie orientale de l'Océan Pacifique, entre les Galápagos et le Golfe de Panama, région où l'alizé n'est pas encore bien établi et où règnent des moussons et des vents variables, la circulation marine est très confuse. Dans l'ensemble, on trouve des eaux stagnantes, qui prennent sans doute peu de part à la circulation générale, et dont la température est souvent très élevée.

En arrivant au voisinage des Philippines, par 10° de latitude Nord environ, le courant équatorial du Nord se divise en deux branches ; l'une va vers le Nord-Ouest se joindre au courant du Japon, et l'autre, orientée vers le Sud, longe la côte orientale de Mindanao à une vitesse de 2 nœuds, puis va se joindre aux eaux du contre-courant équatorial.

La dérive du Pacifique Nord :

La branche principale du Kuroshio qui, vers les latitudes de 35° à 40° Nord, se dirige vers l'Est, diminue rapidement de vitesse à mesure qu'elle s'éloigne du Japon. Ses limites deviennent incertaines aussi bien vers le Nord que vers le Sud. Il ne s'agit plus d'un véritable courant, mais d'une dérive, qui à partir du 180° de longitude, ne dépasse pas une vitesse de 12 milles par jour.

Au moment où le Kuroshio se confond avec la dérive plus lente due à l'impulsion des vents d'Ouest, le Kuroshio est beaucoup moins large, moins profond et dans l'ensemble moins chaud. Du point où le Kuroshio se confond avec la dérive du Pacifique Nord à la côte occidentale de l'Amérique, la distance est de 3500 milles ; ainsi l'influence thermique du Kuroshio sur les rivages nord du Pacifique est très atténuée, mais cependant non négligeable, les régions côtières du Sud de l'Alaska, par des latitudes de 60°, ont en hiver des températures à peine inférieures à 0°C, tandis qu'à la même latitude les régions côtières du Kamtchatka ont des températures de – 15° à – 20°C.

Dérive des eaux du Pacifique Sud :

Entre les parallèles de 40° et de 50° Sud, sous l'influence des vents d'Ouest très fréquents à ces latitudes, on observe, sinon un véritable courant, mais une dérive portant vers l'Est jusqu'aux côtes du Chili. Sa vitesse est très faible, de l'ordre de quelques milles par jour ; elle est plus forte à l'Ouest du 120° méridien de longitude Ouest, surtout pendant l'hiver de l'hémisphère austral, où des vitesses de 1 nœud ont été observées.

Les limites de cette dérive sont indiquées par les lignes de convergence subpolaire vers 55° Sud et subtropicale vers 35° Sud. La partie Sud de la dérive est plutôt dirigée vers le Sud-Est, la partie Nord vers le Nord-Est.

Références :

J. Rouch, Traité d'Océanographie physique. Les mouvements de la mer. Vol. 3. Edit. Payot, Paris, 1948.

National Geographic Society, Washington D.C., 1981

Atlas of Pilot Charts http://msi.nga.mil/NGAPortal/MSI.portal?_nfpb=true&_pageLabel=msi_portal_page_62&pubCode=0003 NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY (USA)

Zones: E. Australia - New Zealand (18)  ; Chile (sensu lato) (26) ; Chile (sensu lato) (26)

|

18 |

26 |

Total species: |

534 (20.8 %) (+ 15 ind.) |

436 (17 %) (+ 1 ind.) |

Calanoida: |

400 |

357 |

other orders |

134 |

79 |

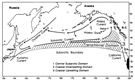

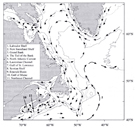

Major currents and circulation patterns around Australia. Major currents and circulation patterns around Australia.

The continent is bounded by the pacific ocean to the east, the indian Ocean to the west and the Southern Ocean to the south.

Issued from : E.S. Poloczanska & al. in Oceanography and Marine Biology: An Annual Review, 2007, 45. [p.409, Fig.2].

Figure courtesy of S. Condie/CSIRO.

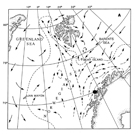

Major bathymetric features of the New Zealand region, surface currents, place names, and topographic features. Major bathymetric features of the New Zealand region, surface currents, place names, and topographic features.

Issued from : Bradford J.M., Roberts P.E., 1978. - Distribution of reactive phosphorus and plankton in relation to upwelling and surface circulation around New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research, 12 (1): [p.3, Fig.1].

388 species are common to the Indian Ocean and the E. Australia - New Zealand zone.

Courants d'Australie :

A la hauteur des îles Samoa, le courant équatorial du Sud paraît se diviser en deux branches : l'une continue vers l'Ouest jusqu'à la Nouvelle-Guinée où les courants sont très influencés par la mousson. Pendant l'été de l'hémisphère Nord, un courant assez fort est dirigé vers l'Ouest et le Nord-Ouest, tandis qu'en hiver on observe un courant faible dirigé vers l'Est.

Entre la Nouvelle-Guinée, les îles Salomon, l'Australie et la Nouvelle-Calédonie, les courants sont confus, faibles et variables suivant les saisons. C'est ainsi que dans de Détroit de Torres, en décembre, janvier et février, le courant est dirigé vers l'Est ; il est dirigé vers l'Ouest pendant le reste de l'année. Ce courant peut être rapide lorsque le vent est fort et souffle dans la même direction. De même sur la côte australienne au Nord de Brisbane, on observe en hiver (de l'hémisphère Nord) un courant vers le Sud-Est, en été, un courant vers le Nord-Ouest.

La deuxième branche du courant équatorial, après avoir traversé l'Archipel des Fidji, passe au Sud de la Nouvelle-Calédonie, atteint la côte australienne à la hauteur de Brisbane. Elle forme alors le Courant australien proprement dit, qui longe la côte à une distance comprise entre 20 et 60 milles, sans atteindre vers le large les parages des récifs Middleton et Elisabeth, no l'île Lord Howe. Le courant australien porte vers le Sud à une vitesse de 0,5 à 3 nœuds, pouvant atteindre par place 4 nœuds. A toucher le rivage, il existe souvent un contre-courant vers le Nord.

Le courant australien s'oriente vers le Sud-Est au large de Sydney, et entre l'Australie et la Nouvelle-Zélande un vaste circuit se dessine en sens inverse des aiguilles d'une montre.

Références :

J. Rouch, Traité d'Océanographie physique. Les mouvements de la mer. Vol. 3. Edit. Payot, Paris, 1948.

National Geographic Society, Washington D.C., 1981

Atlas of Pilot Charts http://msi.nga.mil/NGAPortal/MSI.portal?_nfpb=true&_pageLabel=msi_portal_page_62&pubCode=0003 NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY (USA)

254 species are common to the two southern Pacific zones (i.e.

46.3 % and

58.1 % respectively).

Le Courant du Pérou ou de Humboldt :

La dérive du Pacifique Sud en arrivant près des côtes du Chili se divise en deux branches, vers le 50ème degré de latitude Sud.

La première, connue sous le nom de Courant du Cap Horn entraîne autour de la Terre de Feu à la vitesse de 1 nœud des eaux dont la température est plus élevée que celle du Courant des Falklands à la même latitude.

La deuxième branche, Courant du Pérou ou de Humboldt, coule vers le Nord. On l'observe surtout à partir de Valdivia (40° Sud) jusqu'au Cap Blanco (4°30'S).

Le courant du Pérou n'a qu'une largeur moyenne de 100 à 150 milles. Sa vitesse plus forte sur les côtes du Pérou que sur celles du Chili, dépasse à peine en moyenne un demi nœud. Il est surtout reconnaissable à sa basse température, 15° à 19°, inférieure de plusieurs degrés à la température de surface observée au large à la même latitude, et inférieure parfois d'une dizaine de degrés à la température de l'air au niveau de la mer. Il est également particulièrement riche en phosphates et en nitrates.

Humboldt attribuait ces basses températures à un courant froid venu des régions antarctiques. Ces basses températures des eaux de surface sont attribuées à une remontée des eaux profondes (upwelling) le long des côtes aux pentes abruptes. Les mesures de salinité faites par Sverdrup (1930) montrent que les eaux ne proviennent pas des couches très profondes, mais ne dépassent pas 300 mètres.

Les eaux du courant du Pérou sont moins salées que les eaux du large, et s'en distinguent aussi par leur richesse en phytoplancton qui leur confère une couleur verte, contrastant avec le bleu indigo du large.

Le Courant du Pérou est sujet à des variations importantes qui le rapprochent ou l'écartent de la côte. Dans sa partie Nord ses limites sont variables. Un courant vers le Sud, appelé El Niño, qui se manifeste au Nord du Cap Blanco, surtout au cœur de l'été austral (vers la Noël), descend parfois jusqu'à 12° ou 15° de latitude Sud, faisant disparaître les eaux froides côtières, et changeant pour quelques semaines le climat sec du littoral en un climat pluvieux. Lorsque ce phénomène se produit, cette arrivée des eaux chaudes venant de l'Ouest fait momentanément disparaître ou rejette vers le large le Courant de Humboldt.

Références :

J. Rouch, Traité d'Océanographie physique. Les mouvements de la mer. Vol. 3. Edit. Payot, Paris, 1948.

National Geographic Society, Washington D.C., 1981

Atlas of Pilot Charts http://msi.nga.mil/NGAPortal/MSI.portal?_nfpb=true&_pageLabel=msi_portal_page_62&pubCode=0003 NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY (USA)

Zones: South Africa (E & W), Namibia (5)  ; Gulf of Guinea (sensu lato) (6) ; Gulf of Guinea (sensu lato) (6)

|

5 |

6 |

Total species: |

288 (11.2 %) (+ 3 ind.) |

371 (14.5 %) (+ 2 ind.) |

Calanoida: |

235 |

289 |

other orders |

53 |

82 |

Of the "endemic" to South Africa , 9 species are on the Atlantic side and 2 in the Indian Ocean (Acartia (Acartia) longisetosa, Acartia (Acartia) nana, Centropages natalensis, Centropages tenuicornis, Diaixis centrura).

A conceptual diagram of the circulation of intermediate water in the eastern South Atlantic and around southern Africa (adapted from Boebel et al., 1998 and based on the work of Shannon and Nelson, 1996; Reid, 1989; and others). AB refers to the Agulhas Bank, and AP to the Agulhas Plateau.

A conceptual diagram of the circulation of intermediate water in the eastern South Atlantic and around southern Africa (adapted from Boebel et al., 1998 and based on the work of Shannon and Nelson, 1996; Reid, 1989; and others). AB refers to the Agulhas Bank, and AP to the Agulhas Plateau.

Issued from : Richardson P.L., Lutjeharms J.R.E. & Boebel O., 2003. - Introduction to the "Inter-ocean exchange around southern Africa". Deep Sea Research II, 50 (1): [p.5, Fig.2].

Inverse model mass transport (in Sv) and standard errors for the Agulhas Current system for

the LADCP experiment.

Inverse model mass transport (in Sv) and standard errors for the Agulhas Current system for

the LADCP experiment.

Net mass transport values are displayed on the top, and each individual layer

displays the mass transport associated with it. Red arrows represent diapycnal transports, and blue,

yellow, and orange arrows represent isopycnal transports. Small circular arrows indicate the location of

some of the sampled eddies. PE refers to Port Elizabeth (36°S). EL refers to East London (34°S). PS refers to Port Shepstone (32°S). RB refers to Richards Bay (30°S).

Issued from : Casal T.G.D., Beal L.M., Lumpkin R. & Johns W.E., 2009. - Structure and downstream evolution of the Agulhas Current system during a quasi-synoptic survey in February–March 2003. Journal of Geophysical Research, 114 (C03001): [p.6, Fig.2].

Physical oceanography during the survey. (a) Temperature at 7 m; (b) salinity at 7 m; (c) mean temperature; (d) mean salinity; (e) integrated chlorophyll a; and (f) mean oxygen. Means and integration are over the water column. Visualization performed in Ocean Data View software (Schlitzer, 2008).

Physical oceanography during the survey. (a) Temperature at 7 m; (b) salinity at 7 m; (c) mean temperature; (d) mean salinity; (e) integrated chlorophyll a; and (f) mean oxygen. Means and integration are over the water column. Visualization performed in Ocean Data View software (Schlitzer, 2008).

Issued from : Lebourges-Dhaussy A., Coetzee J., Hutchings L., Roudaut G. & Nieuwenhuys C., 2009. - Zooplankton spatial distribution along the South African coast studied by multifrequency acoustics, and its relationships with environmental parameters and anchovy distribution. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 66. [p.1057, Fig.2].

Horizontal distribution of the global zooplankton. (a) Mean biovolume (mm3 m-3); (b) integrated biovolume (mm3 m-2).

Horizontal distribution of the global zooplankton. (a) Mean biovolume (mm3 m-3); (b) integrated biovolume (mm3 m-2).

Issued from : Lebourges-Dhaussy A., Coetzee J., Hutchings L., Roudaut G. & Nieuwenhuys C., 2009. - Zooplankton spatial distribution along the South African coast studied by multifrequency acoustics, and its relationships with environmental parameters and anchovy distribution. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 66. [p.1058, Fig.4].

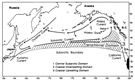

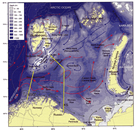

Atlantic currents west of Africa.

Atlantic currents west of Africa.

AC = Angola Current, ABF = Angola Benguela Front, BCC = Benguela Coastal Current, BOC = Benguela Oceanic Current, SECC = South Equatorial Counter Current, SEC = South Equatorial Current, EUC = Equatorial Undercurrent

Issued from : Hogan C., 2012. - Angola-Benguela Front. Retrieved from http://www.eoearth.org/view/article/150063

Zones : Central South Atlantic (12)  ; Brazil-Argentina (SW Atlantic) (13) ; Brazil-Argentina (SW Atlantic) (13)

|

12 |

13 |

Total species: |

337 (13.1 %) (+ 3 ind.) |

397 (15.5 %) (+ 3 ind.) |

Calanoida: |

291 |

278 |

other orders |

46 |

119 |

183 species

are common to the two zones. It is important to note that most of our knowledge of the diversity of Copepoda in the central South Atlantic comes from very old studies (e.g. Wolfenden, 1911).

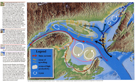

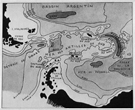

Hydrology from Southwest Atlantic Ocean.

Hydrology from Southwest Atlantic Ocean.

Issued from : E. Boltovskoy in Atlas del Zooplancton del Atlàntico sudoccidental, 1981, ed. D. Boltovskoy, Publ. special des INIPED, Mar del Plata, Argentina. [p.230, Fig.131].

Schematic ocean circulation of the southwestern South Atlantic (modified from Matano et al., 2010) and continental shelf biogeographic provinces (background shading, modified from Balech and Ehrlich (2008) and Boschi (2000)).

Schematic ocean circulation of the southwestern South Atlantic (modified from Matano et al., 2010) and continental shelf biogeographic provinces (background shading, modified from Balech and Ehrlich (2008) and Boschi (2000)).

The red dotted line represents the boundary between the provinces from Spalding et al. (2007), referred to by those authors as Warm Temperate Southwestern Atlantic and Magellan provinces. M.S.= Magellan Strait.

For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version.

Issued from : E.M. Acha, M.D. Viñas, C. Derisio, D. Alemany & A.R. Piola inJ. Mar. Syst., 2020, Volume 204 (103281). [Fig.1].

Ecoregions and marine fronts at the southwestern South Atlantic.

Ecoregions and marine fronts at the southwestern South Atlantic.

Blue lines represent fronts associated with the boundaries of the ecoregions.

A = Plata plume front (33.5 surface isohaline, Piola & al., 2008; Piola & al., 2005).

B = Subtropical front and Brazil-Malvinas Confluence (35 surface isohaline, Piola & al., 2000).

C = Patagonian shelfbreak front (maximum SST gradient for January, Piola & Falabella, 2009).

D = Shallow sea front (Simpson's parameter critical value for summer phyC = 40 J m-3, Bianchi & al., 2005).

E = Estuarine front of Rio da la Plata (27.5 surface isohaline for November-March, Guerrero & al., 2010).

For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version.

Issued from : E.M. Acha, M.D. Viñas, C. Derisio, D. Alemany & A.R. Piola inJ. Mar. Syst., 2020, Volume 204 (103281). [Fig.7].

Ecoregions based on copepod's presence/absence data. Map of the sampling stations assemblages defined by cluster and MDS analysis.

Ecoregions based on copepod's presence/absence data. Map of the sampling stations assemblages defined by cluster and MDS analysis.

Large-scale patterns of pelagic copepods: Occurrence percentage of species expressed in Table 3 and indicator species for each ecoregion in Table 5.

.

Issued from : E.M. Acha, M.D. Viñas, C. Derisio, D. Alemany & A.R. Piola inJ. Mar. Syst., 2020, Volume 204 (103281). [Fig.3].

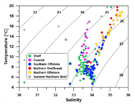

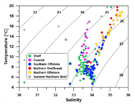

Relationships of the ecoregions with water masses. Sampling stations assemblages defined by CLUSTER and MDS analyses in a temperature-salinity (T/S) space.

Relationships of the ecoregions with water masses. Sampling stations assemblages defined by CLUSTER and MDS analyses in a temperature-salinity (T/S) space.

Temperature and salinity climatological data from the World Ocean Atlas.

For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version.

Issued from : E.M. Acha, M.D. Viñas, C. Derisio, D. Alemany & A.R. Piola inJ. Mar. Syst., 2020, Volume 204 (103281). [Fig.4].

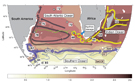

The oceanic circulation around the Agulhas choke point and location of Tara Oceans

stations.

The oceanic circulation around the Agulhas choke point and location of Tara Oceans

stations.

The map shows the location of sampling stations, together with trajectories of the young and old Agulhas rings (TARA_068 and TARA_078, red and green tracks, respectively).The stations here considered as representative of the main basins are (i) TARA_052, TARA_064, and TARA_065 for Indian Ocean; (ii) TARA_070, TARA_072, and TARA_076 for the South Atlantic Ocean, and (iii) TARA_082, TARA_084, and TARA_085 for the Southern Ocean.The mean ocean circulation is schematized by arrows (currents) and background colors [surface climatological dynamic height (0/2000 dbar from CARS2009; www.cmar.csiro.au/cars)] (70). Agulhas rings are depicted as circles.

Issued from : Villar E., Farrant G.K, Follows M. & al. in Science, 2015, 348 (6237). [p.2, Fig.1].

Properties of the young Agulhas ring (TARA_068).

Properties of the young Agulhas ring (TARA_068).

(A) Daily sea surface height around young Agulhas ring station TARA_068 [absolute dynamic

topography (ADT) from www.aviso.altimetry.fr]. R, C1, and C2, respectively, denote the centers of the Agulhas ring and two cyclonic eddies. The contour interval is 0.02 dyn/m. The ADT values are for 13 September 2010. Light gray isolines, ADT < 0.46 dyn/m. The crosses indicate the CTD stations, and the square symbol indicates the position of the biological station TARA_068. The biological station coincides with the westernmost CTD station. ADT is affected by interpolation errors, which is why CTD casts were performed at sea so as to have a fine-scale description of the feature before defining the position of thebiological station (23). Superimposed are the continuous underway temperatures (°C) from the on-board thermosalinograph.

(B) Same as (A) but at the regional scale. Round symbols correspond to biological sampling stations.The contour interval is 0.1 dyn/m.

(C) Seasonal distribution of the median values of the mixed layer depths and temperatures at 10 m (from ARGO) provided by the IFREMER/LOS Mixed Layer Depth Climatology L2 database (www.ifremer.fr/cerweb/deboyer/mld) updated to 27 July 2011.The mixed layer is defined using a temperature criterion. The star symbol represents the young ring station TARA_068. (Inset) Geographic position of the areas used to select the mixed layer and temperature data. The mixed layer depth measured at TARA_068 is outside the 90th percentile of the distribution of mixed layer depths for the same month for both the subtropical (red and magenta) regions.The temperature matches the median for the same month and region of sampling.

(D) Nitrite (NO2) concentrations from CTD casts at different sampling sites (expressed in mmol/m3).

Issued from : Villar E., Farrant G.K, Follows M. & al. in Science, 2015, 348 (6237). [p.5, Fig.4].

Plankton diversity patterns.

Plankton diversity patterns.